The research is conducted inside universities, medical schools, pharmaceutical companies, farms, defense establishments, and commercial facilities that provide animal-testing services to industry. It includes pure research such as genetics, developmental biology, behavioral studies, as well as applied research such as biomedical research, xenotransplantation, drug testing and toxicology tests, including cosmetics testing. Animals are also used for education, breeding, and defense research. The practice is regulated to various degrees in different countries.

The terms animal testing, animal experimentation, animal research, in vivo testing, and vivisection have similar denotations but different connotations. Literally, "vivisection" means the "cutting up" of a living animal, and historically referred only to experiments that involved the dissection of live animals. The term is occasionally used to refer pejoratively to any experiment using living animals; for example, the Encyclopædia Britannica defines "vivisection" as: "Operation on a living animal for experimental rather than healing purposes; more broadly, all experimentation on live animals", although dictionaries point out that the broader definition is "used only by people who are opposed to such work". The word has a negative connotation, implying torture, suffering, and death. The word "vivisection" is preferred by those opposed to this research, whereas scientists typically use the term "animal experimentation".

The earliest references to animal testing are found in the writings of the Greeks in the 2nd and 4th centuries BCE. Aristotle (Αριστοτέλης) (384–322 BCE) and Erasistratus (304–258 BCE) were among the first to perform experiments on living animals. Galen, a physician in 2nd-century Rome, dissected pigs and goats, and is known as the "father of vivisection." Avenzoar, an Arabic physician in 12th-century Moorish Spain who also practiced dissection, introduced animal testing as an experimental method of testing surgical procedures before applying them to human patients.

Animals have been used repeatedly through the history of biomedical research. The founders, in 1831, of the Dublin Zoo—the fourth oldest zoo in Europe, after Vienna, Paris, and London—were members of the medical profession, interested in studying the animals both while they were alive and when they were dead. In the 1880s, Louis Pasteur convincingly demonstrated the germ theory of medicine by inducing anthrax in sheep. In the 1890s, Ivan Pavlov famously used dogs to describe classical conditioning. Insulin was first isolated from dogs in 1922, and revolutionized the treatment of diabetes. On November 3, 1957, a Russian dog, Laika, became the first of many animals to orbit the earth. In the 1970s, antibiotic treatments and vaccines for leprosy were developed using armadillos, then given to humans. The ability of humans to change the genetics of animals took a large step forwards in 1974 when Rudolf Jaenisch was able to produce the first transgenic mammal, by integrating DNA from the SV40 virus into the genome of mice. This genetic research progressed rapidly and, in 1996, Dolly the sheep was born, the first mammal to be cloned from an adult cell.

Toxicology testing became important in the 20th century. In the 19th century, laws regulating drugs were more relaxed. For example, in the U.S., the government could only ban a drug after a company had been prosecuted for selling products that harmed customers. However, in response to the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster of 1937 in which the eponymous drug killed more than 100 users, the U.S. congress passed laws that required safety testing of drugs on animals before they could be marketed. Other countries enacted similar legislation. In the 1960s, in reaction to the Thalidomide tragedy, further laws were passed requiring safety testing on pregnant animals before a drug can be sold.

As the experimentation on animals increased, especially the practice of vivisection, so did criticism and controversy. In 1655, the advocate of Galenic physiology Edmund O'Meara said that "the miserable torture of vivisection places the body in an unnatural state." O'Meara and others argued that animal physiology could be affected by pain during vivisection, rendering results unreliable. There were also objections on an ethical basis, contending that the benefit to humans did not justify the harm to animals. Early objections to animal testing also came from another angle — many people believed that animals were inferior to humans and so different that results from animals could not be applied to humans.

On the other side of the debate, those in favor of animal testing held that experiments on animals were necessary to advance medical and biological knowledge. Claude Bernard, known as the "prince of vivisectors" and the father of physiology—whose wife, Marie Françoise Martin, founded the first anti-vivisection society in France in 1883—famously wrote in 1865 that "the science of life is a superb and dazzlingly lighted hall which may be reached only by passing through a long and ghastly kitchen". Arguing that "experiments on animals ... are entirely conclusive for the toxicology and hygiene of man...the effects of these substances are the same on man as on animals, save for differences in degree," Bernard established animal experimentation as part of the standard scientific method. In 1896, the physiologist and physician Dr. Walter B. Cannon said "The antivivisectionists are the second of the two types Theodore Roosevelt described when he said, 'Common sense without conscience may lead to crime, but conscience without common sense may lead to folly, which is the handmaiden of crime.' " These divisions between pro- and anti- animal testing groups first came to public attention during the brown dog affair in the early 1900s, when hundreds of medical students clashed with anti-vivisectionists and police over a memorial to a vivisected dog. In 1822, the first animal protection law was enacted in the British parliament, followed by the Cruelty to Animals Act (1876), the first law specifically aimed at regulating animal testing. The legislation was promoted by Charles Darwin, who wrote to Ray Lankester in March 1871: "You ask about my opinion on vivisection. I quite agree that it is justifiable for real investigations on physiology; but not for mere damnable and detestable curiosity. It is a subject which makes me sick with horror, so I will not say another word about it, else I shall not sleep to-night." Opposition to the use of animals in medical research first arose in the United States during the 1860s, when Henry Bergh founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), with America's first specifically anti-vivisection organization being the American AntiVivisection Society (AAVS), founded in 1883. Antivivisectionists of the era generally believed the spread of mercy was the great cause of civilization, and vivisection was cruel. However, in the USA the antivivisectionists' efforts were defeated in every legislature, overwhelmed by the superior organization and influence of the medical community. Overall, this movement had little legislative success until the passing of the Laboratory Animal Welfare Act, in 1966.

The terms animal testing, animal experimentation, animal research, in vivo testing, and vivisection have similar denotations but different connotations. Literally, "vivisection" means the "cutting up" of a living animal, and historically referred only to experiments that involved the dissection of live animals. The term is occasionally used to refer pejoratively to any experiment using living animals; for example, the Encyclopædia Britannica defines "vivisection" as: "Operation on a living animal for experimental rather than healing purposes; more broadly, all experimentation on live animals", although dictionaries point out that the broader definition is "used only by people who are opposed to such work". The word has a negative connotation, implying torture, suffering, and death. The word "vivisection" is preferred by those opposed to this research, whereas scientists typically use the term "animal experimentation".

The earliest references to animal testing are found in the writings of the Greeks in the 2nd and 4th centuries BCE. Aristotle (Αριστοτέλης) (384–322 BCE) and Erasistratus (304–258 BCE) were among the first to perform experiments on living animals. Galen, a physician in 2nd-century Rome, dissected pigs and goats, and is known as the "father of vivisection." Avenzoar, an Arabic physician in 12th-century Moorish Spain who also practiced dissection, introduced animal testing as an experimental method of testing surgical procedures before applying them to human patients.

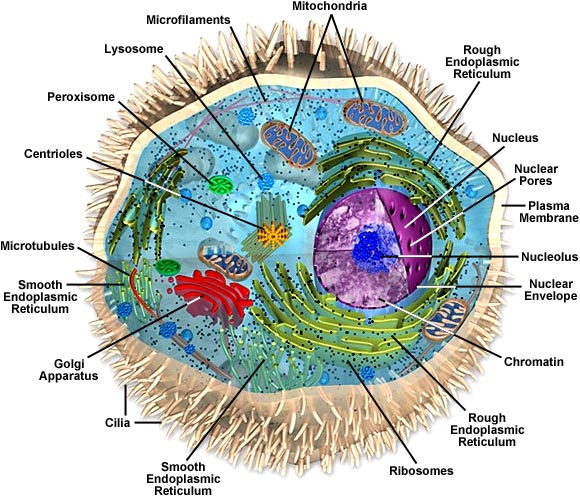

Cell components (we\x26#39;ve |  Luckily, both of my kids |  Simple Animal Cell |  She did an animal cell model |  an animal cell model as an |

A Very Impressive Animal Cell |  Anatomy Models \x26gt; Kids Corner |  Make a animal cell model One | 3-D Animal Cell Model Made |  an animal cell. |

As the experimentation on animals increased, especially the practice of vivisection, so did criticism and controversy. In 1655, the advocate of Galenic physiology Edmund O'Meara said that "the miserable torture of vivisection places the body in an unnatural state." O'Meara and others argued that animal physiology could be affected by pain during vivisection, rendering results unreliable. There were also objections on an ethical basis, contending that the benefit to humans did not justify the harm to animals. Early objections to animal testing also came from another angle — many people believed that animals were inferior to humans and so different that results from animals could not be applied to humans.

Clevershoppers.com \x26middot; Learning |  animal cell to your child |  Tedco 4D Science Animal Cell |  Biosigns Animal Cell Model | A Cake Cell Model. okay i have |

Animal Cell Model Biology |  All plants and animals and |  A 3-D cell model will help |  models of animal cells out |  3- D cell model project I need |

No comments:

Post a Comment